Don Fornes

Executive Summary

In construction, defaults and incidents can mean the difference between success and failure. The typical default costs 1.5x to 3.0x the original subcontract value, not to mention the impact of project delays and reputational damage.

Unfortunately, subcontractors introduce default risk through financial instability, safety incidents, or poor-quality work. In the early days of a general contractor (GC) business, senior management has close relationships with a limited number of subcontractors. As the organization grows and works with more subcontractors, managing these relationships and their risks becomes difficult.

Once a GC manages over a dozen subcontractors, mitigating risk requires a disciplined, scalable prequalification process. GCs that implement effective prequalification are eventually well-positioned to adopt subcontractor default insurance (SDI), through which they take on more risk with the potential reward of lower insurance costs and higher profits. A similar opportunity is available in property and casualty, as contractor-controlled insurance programs (CCIPs) can shift the risk (and reward) of safety incidents to GCs.

This document provides a comprehensive guide to subcontractor prequalification. By implementing the strategies and tools outlined in this guide, GCs can reduce default and safety risk, enhance project outcomes, foster stronger subcontractor relationships, and build a culture of continuous improvement that benefits GCs, owners, and subcontractors.

Importantly, prequalification should not produce binary, pass/fail decisions. The result should not be just, “Yes. We can use this subcontractor,” or “No. This subcontractor is too risky.” Instead, GCs should use prequalification to support collaboration with subcontractors and mitigate risk throughout each project's lifecycle.

We call this “Contractor Success.”

Why Subcontractors Default

Defaults arise from financial, operational, and external challenges, but often in the context of the subcontractor overextending themselves in pursuit of more business. As one leading SDI underwriter aptly noted, "Subcontractors don’t die of starvation; they die of overeating." Typical reasons for default include:

Lack of Industry Experience

Subcontractors unfamiliar with specific industry requirements (e.g., hospitals) underestimate complexity and fail to deliver.

Geographic Stretch

Operating in unfamiliar regions exposes subcontractors to unfamiliar regulations, insufficient manpower, and logistical risks.

Financial Instability

Cash flow issues and unsustainable debt burdens leave subcontractors vulnerable to unexpected expenses or delays.

Business Practices

Inconsistent management or unethical practices undermine subcontractor reliability and put reputations at risk.

Poor Quality

Substandard workmanship results in costly rework, delays, and increased safety exposure.

Labor Constraints

Skilled labor shortages and rising costs hinder subcontractors' ability to meet project demands.

The "Three Cs" of Underwriting

Traditionally, surety bond underwriters have used three fundamental criteria – Character, Capacity, and Capital – to assess the risk of subcontractor default. These principles can be effectively applied to a GC’s prequalification process.

Character

This evaluates the subcontractor's reputation, ethical standards, safety, and reliability. During prequalification, character assessment involves reviewing the subcontractor's past performance, default or litigation history, and ability to maintain strong client relationships.

Capacity

Capacity measures the subcontractor's resources and technical ability to execute a successful project. This includes evaluating project experience, manpower, and operational systems to ensure the subcontractor can meet the specific demands of the job.

Capital

Capital refers to the subcontractor's financial health and ability to sustain operations during unforeseen challenges. To ensure sufficient financial resilience, financial statements, backlog, borrowing capacity, and surety bonding are analyzed.

Assessing Character

The key steps and considerations when assessing the character of a subcontractor include:

- Confirm Corporate Standing. Verify the corporate entity's good standing by reviewing its formation documents (e.g., articles of incorporation) and requesting a certificate of good standing from its state of incorporation. Understand whether it has a parent company or has recently changed its name, which may impact the risk profile.

- Review Officers and Directors. Gather a list of the subcontractor's officers and directors and investigate whether they own related companies or have been involved in problematic entities. This ensures they are not using "shell game" tactics to obscure risks.

- Verify Licenses and Certifications. Ensure the subcontractor holds all required licenses and certifications to perform their scope of work. Ensure they are specific to the project location and not expired.

- Confirm Good Standing with Unions. If the subcontractor uses union labor, require a letter of good standing from each union. Failure to pay union dues is a leading indicator of financial instability.

- Review Master Subcontractor Agreement. It’s important to have easy access to contract documents during prequalification to confirm they are fully executed and to understand the terms of the relationship.

- Confirm Disadvantaged Business Certificates. If the subcontractor is a disadvantaged business entity, such as a small business, woman-owned business, minority-owned business, etc., gather certificates to validate that status.

- Inquire About Past Defaults. Ask directly about any past defaults on projects. A pattern of defaults can signal significant operational or financial issues. Require the subcontractor to attest to fully and truthfully answering these questions.

- Investigate Litigation History. Request details of past and current litigation involving the subcontractor. Ongoing lawsuits can indicate unresolved disputes that may affect project performance. Verify using third-party legal databases.

Article of Incorporation

W-9 Form

Master Subcontractor Agreement

Default & Litigation Questionnaire

Certificate of Good Standing

Licenses and Certifications

Disadvantaged Business Certificates

Assessing Capacity

Assessing a subcontractor's capacity is essential to ensure they can meet a project's demands without overextending their resources. This involves evaluating their labor force, industry expertise, geographic experience, and operational capabilities.

- Confirm Contract Size Experience. Confirm that the subcontractor has successfully completed projects of similar size and scope. This ensures they can manage the complexities and resource demands of important projects.

- Review Industry Experience. Assess the subcontractor's experience in the relevant project’s industry. Ensure the assigned project manager and team have the required expertise, as these learnings reside at the team or individual level.

- Assess Geographic Experience. Verify the subcontractor’s familiarity with local building codes and regulations. Request a list of completed projects in the region and evaluate the subcontractor’s ability to leverage local relationships.

- Determine Labor Capacity. Conduct workforce assessments by requesting staffing plans, historical workforce data, and manpower schedules. Compare the subcontractor’s manpower trends against their backlog to identify signs of overextension.

Project Portfolio, including:

• Contract Size

• Industry

• LocationManpower Schedules

Project Team Resumes

Backlog Schedules

Assessing Capital

Understanding a subcontractor's financial strength is critical to the prequalification process. It ensures the subcontractor can sustain operations, manage unforeseen challenges, and deliver projects successfully. This evaluation focuses on liquidity, profitability, efficiency, leverage, and backlog.

Balance Sheets

Statements of Cash Flows

Work-Not-Started Schedules

Income Statements

Work-in-Progress Schedules

Obtaining financial statements from subcontractors can be a sensitive process, as these documents are considered highly confidential. Many subcontractors may be hesitant to share this information due to concerns about privacy or misuse. To address this, prequalification managers should:

- Clearly communicate the purpose of the request;

- Identify the specific people who will have access to financials;

- Document the security protocols in place to protect the information; and,

- Offer a mutual non-disclosure agreement (NDA) to build trust.

With financial statements in hand, prequalification analysts can calculate a series of financial ratios, which provide insight into the subcontractor’s financial viability. Below, we explain twenty useful ratios and how to calculate them. We also provide thresholds for moderate and high risk and the relevant Construction Financial Management Association (CFMA) benchmark.

Liquidity

Liquidity measures the subcontractor's ability to meet short-term financial obligations. This ensures the subcontractor can address immediate and unexpected expenses. Four ratios help identify liquidity risks.

Ratios | Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

Current Ratio (Current Assets / Current Liabilities) | Measures a company's ability to pay short-term obligations with its current assets. | <1.0 <1.5 1.6 |

Quick Ratio ((Current Assets - Inventory) / Current Liabilities) | Evaluates a company's capacity to meet short-term liabilities with its most liquid assets. | <0.8 <1.0 1.4 |

Cash Ratio (Cash + Cash Equivalents / Current Liabilities) | Assesses a company's ability to pay off short-term debt with cash and cash equivalents. | <0.3 <0.4 0.5 |

Days of Cash (Cash and Cash Equivelents) * 360) + Revenue | Indicates how many days a company can continue to operate using its available cash. | <30 <45 24 |

Profitability

Profitability ratios assess the subcontractor's ability to generate income from operations. An unprofitable subcontractor won’t remain in business long. Four ratios help illuminate profitability concerns.

Ratios | Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

Gross Profit Margin (Revenue - Cost of Goods Sold) / Revenue) | The percentage of revenue, after all expenses, indicates the ability to generate profit from operations. | <15% <20% 16% |

Net Profit Margin (Net Income / Revenue) | The percentage of revenue, after all expenses, indicates the ability to generate profit from operations. | <0.0% <5.0% 8.0% |

Return on Assets (Net Income / Total Assets) | Assesses efficiency in using assets to generate profit. | <2.0% <4.0% 12.0% |

Return on Equity (Net Income / Shareholder Equity) | Indicates return generated on shareholder equity. | <5% <10% 31% |

Efficiency

Efficiency ratios evaluate how effectively the subcontractor manages assets and working capital. They highlight operational efficiency and the ability to maintain a stable cash cycle. Four ratios demonstrate a subcontractor’s efficiency.

Ratios | Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

Working Capital Turnover (Revenue / (Current Assets - Current Liabilities) | Measures how effectively working capital is used. A low turnover below 2.0 may indicate inefficiency in utilizing resources. | <2.0 <4.0 7.4 |

Tangible Equity to Liabilities ((Total Equity - Intangibles) / Total Liabilities) | Indicates financial stability and risk exposure. A ratio below 0.5 may suggest over-leverage. | <0.5 <0.8 1.9 |

Receivables Turnover (Days) ((Accounts Receivable / Revenue) x 365) | Shows how quickly receivables are collected. A turnover exceeding 60 days may indicate cash flow concerns. | >90 >45 56 |

Payables Turnover (Days) ((Accounts Payable / Cost of Goods Sold) x 365) | Highlights how quickly payables are settled. A turnover exceeding 60 days may indicate strained supplier relationships. | >75 >45 33 |

Leverage

Leverage ratios examine the subcontractor's debt levels and their impact on financial stability. They offer insights into the subcontractor’s capital structure and corresponding financial risk. Four ratios help identify whether a subcontractor is over-leveraged.

Ratios | Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

Debt to Equity (Total Debt / Shareholder Equity) | Assesses the level of debt relative to equity. A ratio above 2.0 indicates high financial leverage and risk. | >3.0 >2.0 1.3 |

Debt to Assets (Total Debt / Total Assets) | Measures debt as a percentage of total assets. A ratio above 50% suggests potential over-leverage. | >0.7 >2.0 0.3 |

Debt to Capital (Total Debt / (Total Liabilities + Shareholder Equity)) | Indicates the proportion of debt in the capital structure. A ratio above 60% signals high dependence on debt. | >0.8 >0.6 0.4 |

Debt to EBITDA (Total Debt / Earnings Before Interest, Depreciation & Amortization) | Evaluates the ability to cover debt with cash flow. A ratio above 5.0 may indicate excessive leverage. | >5.0 >3.0 2.0 |

Backlog

Backlog measures the volume and profitability of work the subcontractor has under contract but not yet completed. While too little backlog has obvious negative implications, a more common issue is that the subcontractor has more backlog than capacity to deliver work. Four ratios put a subcontractor’s backlog in perspective.

Ratios | Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

Backlog in Months (Total Backlog / (Total Revenue / 12) | Indicates the length of work secured but not completed. A backlog exceeding 24 months may indicate overextension. | >15 >12 8.7 |

Backlog as a % of Revenue (Total Backlog / Revenue) | Presents the backlog relative to the company’s last fiscal year revenue, indicating if they have taken on more work than they typically deliver. | >200% >150% 100% |

Backlog to Working Capital (Total Backlog / (Current Assets - Current Liabilities) | Assesses backlog relative to available working capital. A ratio above 10:1 suggests potential resource strain. | >10 >8 6 |

Backlog Gross Profit Margin ((Total Backlog - Estimated Cost to Complete) / Total Backlog) | Measures profit margin within the backlog. A gross margin below 10% suggests potential profitability issues. | <10% <15% 20% |

Setting Subcontractor Award Limits

A key output of a prequalification assessment is the calculation of how much business can be safely awarded to a subcontractor. This requires a limit for each project, as well as an aggregate limit across all projects awarded to the subcontractor. Importantly, limits are mostly science and a bit of art. Financial analysis can calculate an approximate amount, but it’s important to consider qualitative factors, such as experience and capacity considerations, as limits are finalized.

Single Project Limits

Several approaches can be used to calculate single-project limits:

- The Average Three Largest Contracts. By averaging the values of the subcontractor's three largest contracts over the past three years, prequalification managers can gauge the subcontractor's comfort zone. This method is useful for assessing a subcontractor's historical performance with similar-sized projects.

- Surety Underwriter Limit. Surety bond underwriters typically set a single project limit based on their detailed evaluation of the subcontractor's financial and operational capacity. This value provides a reliable benchmark backed by professional underwriting standards.

- Last Fiscal Year Revenue. Using 25% of the subcontractor's annual revenue helps ensure that the awarded project is proportional to the subcontractor's overall financial activity. This approach ensures one project isn’t the sole source of the subcontractor’s viability.

- Cash Balance + Available Line of Credit. This method assesses liquidity and financial flexibility by factoring in cash reserves and credit availability. Multiplying the sum by 3.0 provides a conservative estimate of the subcontractor's capacity to finance a single project.

- Latest Working Capital. Working capital, a measure of short-term financial health, is a critical factor in determining project capacity. Multiplying this value by 3.0 ensures the subcontractor has adequate resources to manage project demands without financial strain.

Single project limits can be determined by calculating various financial metrics and then averaging, weighting, or prioritizing the outputs.

By applying one or more of these methods, prequalification managers can establish a contract award limit that aligns with the subcontractor's financial and operational capabilities. One recommended approach is to calculate all the proposed limits and then select the lowest value as the award limit, providing the most conservative risk mitigation. Another method is to take the average of the values. Alternatively, prequalification managers may apply weighting to the lowest three values, take the sum of the weighted values, and use the result to balance conservatism with flexibility.

Finally, it might make sense to discount these limits further if the contractor’s financials are not audited. Financial ratios are only as good as the data input, and if the contractor’s financials are not audited, it is possible that there are inadvertent or even deliberate inaccuracies.

Setting an Aggregate Contract Limit

Determining a subcontractor's aggregate contract limit – the total value of all contracts that can be awarded – can be accomplished in a few different ways, including:

- Surety Underwriter Aggregate Limit. The subcontractor's aggregate bonding limit, set by their surety bond underwriter, reflects the underwriter's assessment of the subcontractor's financial and operational capacity to handle multiple projects simultaneously.

- Last Fiscal Year Revenue. Using 50% of the subcontractor's annual revenue provides a proportional measure of the total workload they can manage without overextension, assuming the GC is not their only client. This approach ensures the aggregate limit aligns with the subcontractor's financial throughput.

- Cash Balance + Available Line of Credit. This method evaluates the subcontractor's liquidity and financial flexibility. Summing their cash reserves and available credit and multiplying by 5.0 estimates a maximum sustainable aggregate workload.

- Latest Working Capital. Working capital, a key indicator of short-term financial health, is multiplied by 7.0 to establish a conservative estimate of the subcontractor's aggregate capacity.

- Total Shareholders' Equity. Using 4.0 times the subcontractor's total shareholders' equity ensures that the aggregate limit reflects the subcontractor's long-term financial stability and capacity to absorb project-related risks.

Like single-project limits, aggregate limits can be determined by calculating various financial metrics and then averaging, weighting, or prioritizing the outputs.

Prequalification managers may calculate limits using all of these methods to set an aggregate contract limit and select the lowest value for the most conservative risk mitigation. Alternatively, managers might apply weighting to the lowest three values to create a balanced approach.

The Role of Safety

Safety risks pose significant hazards to workers and anyone near the project, creating a human cost and jeopardizing the project timeline and budget. A severe safety incident can lead to a work stoppage as investigations are undertaken. Insurance claims and litigation can lead to unprofitable CCIPs and drive up premiums in the future.

Prequalification plays an important role in ensuring subcontractors have a strong safety culture and put the right measures in place to ensure a safe project. Traditionally, prequalification focused primarily on financial and operational risks but only assessed a few “lagging” safety indicators. These safety metrics provide a valuable measure of past safety performance, but to truly understand safety risks and take action to mitigate them, GCs must assess leading indicators, such as safety management systems, program elements, and advanced initiatives the subcontractor may or may not have in place.

OSHA 300A

Safety Manuals

OSHA 300

EMR Letter

Past Safety Performance

Lagging Indicators are the historical metrics that detail a subcontractor’s safety record. While they are less predictive of future performance than leading and behavioral indicators, they still play a valuable role in risk assessment.

Indicator | Definition & Purpose | Thresholds |

|---|---|---|

EMR | Experience Modification Rate is a numeric representation of a company's safety record compared to industry averages. An EMR of 1.0 is average; values below 1.0 indicate better-than-average performance, while values above 1.0 suggest higher risk. Calculated by insurance carriers based on past claims and payroll size over three years. | >1.15 >1.00 1.00 |

DART | Days Away, Restricted Duty, or Job Transfer Rate measures workplace injuries or illnesses causing an employee to miss work, resulting in restricted or modified duty, or transfer to another job. Calculated as (Number of DART Cases × 200,000) ÷ Total Employee Hours Worked. The multiplier represents 100 employees working 40 hours a week for 50 weeks. | >3.00 2.00 - 3.00 <2.00 |

TRIR | Total Recordable Incident Rate is a standard metric for workplace safety, showing the rate of OSHA-recordable incidents per 200,000 employee hours worked. Calculated as (Total Recordable Cases × 200,000) ÷ Total Hours Worked. | >3.00 >2.00 - 3.00 <2.00 |

Citations

Finally, review each subcontractor's OSHA citation history to if their behavior demonstrates a different approach to safety than their incident history would suggest. Look for the frequency, severity, and types of violations, paying close attention to repeat or willful violations, which may indicate systemic safety issues. Reviewing whether violations have been resolved and if corrective actions were implemented demonstrates the subcontractor’s responsiveness and willingness to improve safety practices.

Leading Indicators

Leading indicators are proactive measures that help organizations identify and mitigate potential safety risks before incidents occur. Unlike lagging indicators, which reflect past incidents, leading indicators look toward future outcomes by analyzing the presence and effectiveness of safety management systems, program elements, and advanced initiatives.

Safety Management Systems

An effective safety management system provides a structured approach to managing safety, encompassing policies, procedures, and organizational structures for hazard identification and risk control. Key components include employee training programs, management commitment, and continuous improvement processes. GCs can assess subcontractors' safety management systems by reviewing safety manuals for the presence and sophistication of these systems.

Example question:

Does your company have an audit, inspection, and hazard identification and reporting program or process?

Program Elements

These are specific safety programs targeting particular hazards or activities within an organization. These include confined space entry procedures, fall protection plans, and emergency response protocols. GCs can assess these by asking subcontractors to answer questions related to these program elements, with affirmative responses requiring supporting documentation to verify the existence and adequacy of such programs.

Example question:

Does your company have a program, policy, procedure, or safety statement that addresses the hazards associated with work at heights/fall exposures?

Advanced Initiatives

These initiatives go beyond basic compliance and reflect an organization's commitment to safety excellence. They may include return-to-work programs for injured employees, substance abuse prevention programs, and participation programs like OSHA's Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP). Evaluate subcontractors on the presence of such advanced initiatives, recognizing their role in fostering a proactive safety culture.

Example question:

Does your company have a ‘return to work’ program for employees who have been injured?

By focusing on these leading indicators, organizations can proactively address potential safety risks, ensuring a safer working environment and reducing the likelihood of incidents.

The Role of Quality

The construction industry recognizes a clear link between a subcontractor’s quality of work and their financial health. Poor-quality work that results in the need for rework has clear implications for both safety and financial health. There is also a direct impact on schedule and cost that can stress the subcontractor’s viability.

If a significant amount of rework is required due to poor quality workmanship, acceptance and installation of incorrect materials, installation of damaged materials, etc., the financial impacts can be extremely damaging. In a worst-case scenario, a subcontractor that is teetering can default as a result of the costs that result from poor quality, the need to perform rework, and the subcontractor bearing the brunt of the associated costs to replace their work.

It is estimated that 15-30% of defaults are driven by issues with quality. However, quality-driven defaults are typically much more expensive to remedy. A typical default requires 1.6x the original cost to remediate. But when a default is driven by quality issues, it typically costs 2.0x to 2.5x the original cost because of the rework required. Also, rework introduces significant safety risks as poorly installed work must be removed/demolished and replaced, often with increased schedule and cost pressure. This exposes labor to safety risks three times over.

Because of the significant impacts that quality can have on project schedule, cost, and safety it is important that GCs evaluate each subcontractor’s level of sophistication and approach to managing quality. GCs should evaluate quality in a similar manner as financial, default, and safety risks are assessed during prequalification. Some key questions to answer regarding a subcontractors approach to quality include:

- Does the subcontractor have a formal quality control program?

- Does the subcontractor have a quality control director/manager, department, or team?

- Does the subcontractor have a defined process for conducting quality inspections?

- Does the subcontractor define specific inspection hold points where work must be inspected before progressing?

- Does the subcontractor have a defined process for accepting materials that are delivered to a project or job site to ensure that the correct materials have been delivered, the materials are in good condition, and a plan is in place to store materials until such time as they are installed?

- Does the subcontractor have a defined process for managing rework?

Ongoing evaluation of a subcontractor’s ability to deliver quality work throughout the course of construction is equally important. GCs should conduct regular quality control inspections. Aggregated data from quality control inspections further informs the GC with regard to a subcontractors ability to deliver quality work and respond to and correct any deficiencies.

Finally, at the end of each subcontractor’s scope of work the GCs project team should evaluate overall performance relative to quality. Aggregated evaluations allow the GC to understand how often rework is required, what the main drivers behind the need to perform rework are, estimated costs associated with rework, and any resulting schedule impacts.

A formal approach to assessing and monitoring subcontractor performance relative to quality will help to reduce risk and allow for better, more informed decision making moving forward.

The Ultimate Goal: Contractor Success

Traditionally, prequalification has been delivered as a discrete step in preconstruction, resulting in a decision to move forward with a subcontractor or not. This is marginally effective, as it rules out high-risk subcontractors. However, the reality is that GCs are often forced to work with a subcontractor regardless of their risk profile. This might result from an owner’s mandate to use local or diverse contractors, or that subcontractor might be the only subcontractor with specific skills and availability.

This reality requires GCs to shift their mindset on prequalification, from a binary decision made during preconstruction to an ongoing, collaborative process designed to help contractors improve.

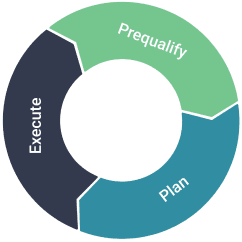

Delivering Contractor Success requires a structured, three-step process that spans the entire lifecycle of the subcontractor relationship: Prequalify, Plan, and Execute. Put simply, GCs must answer three simple questions:

- What are this contractor’s risks?

- What’s our plan to mitigate the risks?

- Is the project team executing the plan?

Prequalify

Rather than a pass/fail system based on past performance, GCs should evaluate subcontractors to understand how the subcontractor can improve going forward. This holistic approach provides insight into the programs, systems, and current behaviors that will drive tomorrow’s outcomes rather than looking solely at what happened in the past. After all, we can’t change the past, but we can improve our readiness for the future.

Plan

Once subcontractor risks are identified, a targeted risk mitigation plan (RMP) can be created for each concern. For safety risks, a corrective action plan (CAP) might require the subcontractor to add training, increase supervision, or improve reporting. For financial or liquidity risks, an exception management plan may include using joint checks to ensure payments go directly to suppliers or having the GC purchase critical materials upfront to alleviate cash flow pressures. These strategies allow proactive risk management, ensuring subcontractors meet standards while maintaining financial and operational stability.

Execute

To execute these plans effectively, ongoing monitoring and accountability are essential. For safety risks, this involves regular onsite inspections to confirm subcontractors are following the CAP and exhibiting safe behaviors. Safety professionals play a key role in observing practices, ensuring compliance, and providing feedback. Project teams can intervene if unsafe practices and trends emerge, reinforcing elements outlined in corrective action plans.

Transparency and oversight are critical for financial or operational risks. Senior executives should know which exception management plans are active and understand the level of financial exposure across projects. This includes knowing which project managers are accountable for these risks and ensuring they follow RMPs. Regular check-ins align project managers with risk management goals, ensuring proactive action on vulnerabilities.

When a subcontractor completes their scope of work, the GC’s project team collaboratively evaluates the subcontractor’s overall performance. The evaluation often covers many aspects of project delivery, including the performance of subcontractor project team members, ability to manage and maintain schedule, quality of work, change order management, safety, and more. Visibility into completed evaluations helps future project teams make better decisions and avoid repeated mistakes.

Importantly, aggregated data from in-field inspections, incident tracking, and evaluations inform future decisions supporting continuous improvement and Contractor Success.

Contractor Success Maturity Model

Contractor Success is a bold vision with a strong return on investment, but it’s unrealistic to think a GC can achieve this objective in one fell swoop. Instead, GCs should develop this standard of excellence through a journey we call the Contractor Success Maturity Model.

This journey involves four distinct phases, each building on the previous one and representing increasing sophistication and commitment to full-lifecycle risk mitigation.

- Relationship Management. Get organized with onboarding subcontractors, signing MSAs, gathering licenses, managing contacts, and handling other administrative tasks.

- Prequalification Assessments. Perform a more sophisticated analysis of subcontractor experience, capacity, and financials. Begin implementing RMPs and CAPs to mitigate identified risks.

- Risk Management Plans. Fully integrate RMPs, CAPs, evaluations, and inspections to ensure execution. Feed insights from subcontractor interactions into dynamic profiles for continuous improvement.

- Advanced Assessments. Conduct deeper evaluations of safety, quality, and environmental risks. Subcontractors should begin to recognize continuous improvement.

Progressing through the Contractor Success Maturity Model requires a strategic and deliberate approach. GCs should focus on building organizational buy-in at each phase and fostering trust with subcontractors to ensure smooth transitions between phases.

By thoughtfully moving through these phases, GCs can create a culture of continuous improvement and risk mitigation that benefits all project stakeholders. At the same time, each progression unlocks new opportunities, such as adopting SDI and CCIP insurance programs.

Conclusion

Contractor prequalification is not just a procedural step; it is a cornerstone of risk management and project success. By systematically evaluating subcontractors and progressing through the phases outlined in full-lifecycle risk mitigation, GCs can reduce risks, improve project outcomes, and foster collaborative relationships with subcontractors.

This guide underscores the importance of viewing prequalification as an ongoing process. Through continuous monitoring, re-evaluation, and clear communication, GCs can ensure that prequalification evolves into a dynamic tool for mitigating risks and driving improvement. Ultimately, these efforts help build a resilient construction ecosystem where safety, quality, and financial stability are prioritized.

By following this guide, GCs can build stronger subcontractor relationships, enhance project outcomes, and establish a culture of continuous improvement and shared success.